Have you ever heard of Pavlovian conditioning? What about the Skinner box? or Bandura’s bobo-doll?

Even if these terms are unfamiliar, you’ve likely experienced the joy of savoring a dish your grandmother used to prepare, the unease accompanying a dentist visit, or the melancholy that washes over you when Spotify plays “All Too Well.” In this article, we will delve into the fascinating world of associative learning, exploring the mechanisms behind it, how it shapes our experiences and emotions, and what triggers certain memories.

Table of Contents

Exploring Associative Learning

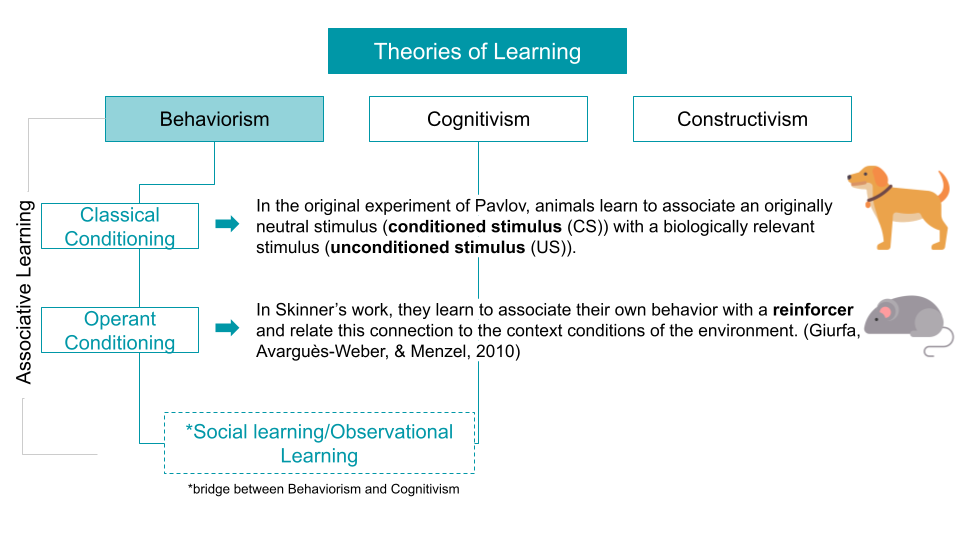

The intricate network of connections that links seemingly unrelated stimuli, events, and emotions is central to the complexity and wonder of the human mind. This cognitive phenomenon, often referred to as “[associative learning],” encompasses situations where the combination of stimuli leads to behavioral changes (Houwer & Hughes, 2020). Within Behavioral Psychology, associative learning is a pivotal process through which individuals gather and store information by linking stimuli (A and B), responses, and consequences. It serves as the foundation of our understanding of causality and significantly influences our perception of the external world. Moreover, associative learning underpins most of our adaptive behaviors, as we recognize associations with either positive or negative outcomes (Christian, 2010).

To simplify the variables of associative learning, we can refer to the diagram below.

Types of Associative Learning: How We Learn?

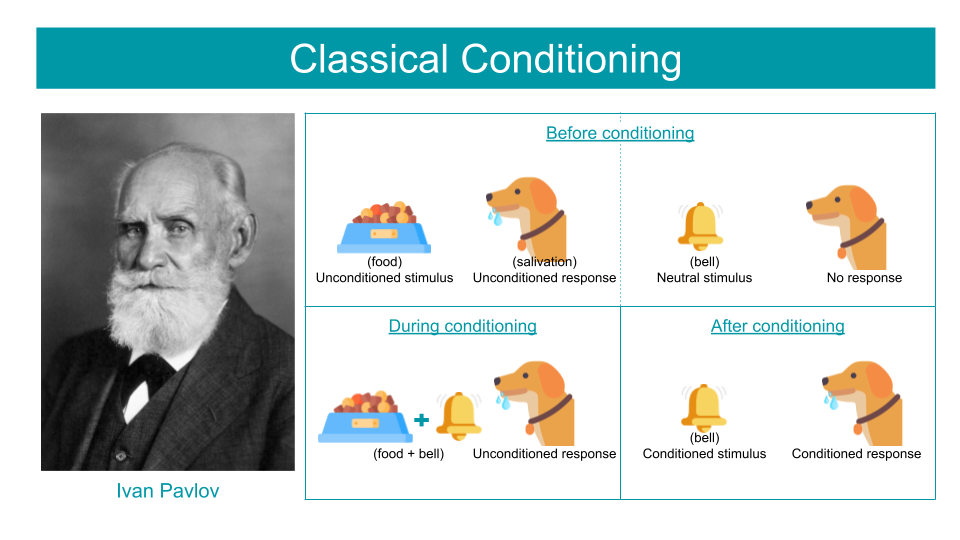

One of the foundational components of associative learning is Ivan Pavlov’s Classical Conditioning. Through his iconic experiment, the Russian physiologist revealed that dogs began to salivate (unconditioned response) not only when they saw food (unconditioned stimulus) but also when they saw the lab assistant who fed them or their food dish (a neutral stimulus). With time, the dogs associated the sight of the lab assistant (conditioned stimulus) with the arrival of food. Pavlov further refined this conditioning by introducing a bell as the conditioned stimulus, resulting in the dogs salivating (conditioned response) at the sound of the bell, even in the absence of food (Bryne, 2013). This experiment demonstrated how organisms could learn to respond to new stimuli by forming associations, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of learning and behavior.

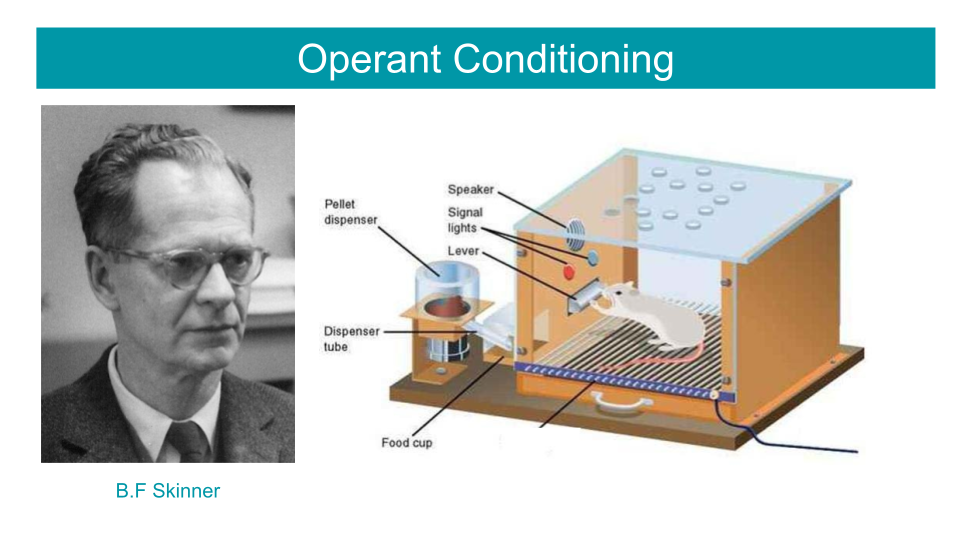

Another facet of associative learning is Operant Conditioning, championed by the American psychologist Burhus Frederick Skinner. While Pavlov focused on associating stimuli and responses, Skinner utilized controlled environments to investigate the relationship between behavior and its consequences. His Skinner boxes revealed that both positive and negative reinforcements could modify behavior.

For instance, when a rat received a food reward every time it pressed a lever, it quickly learned to press it repeatedly or increase the frequency of the behavior due to positive reinforcement (food).

Here’s a TED-Ed video to learn more about the difference between Classical and Operant Conditioning.

Associative Learning in Action

In education, associative learning plays a pivotal role, especially in classrooms with younger students. Classical and Operant conditioning prove effective in building rapport, establishing rules, and instilling routines within physical or virtual classrooms. Creating positive associations, such as making school enjoyable or group participation rewarding, can enhance academic achievement and foster good behavior among students. Simple rewards like words of affirmation, star stamps, and tokens can motivate students to exhibit desirable behaviors. Conversely, failure to establish positive associations, such as publicly punishing a disruptive student, can lead to poor performance and more frequent, uncontrollable misbehavior.

Conversely, failure to establish positive associations, such as publicly punishing a disruptive student, can lead to poor performance and more frequent, uncontrollable misbehavior.

The power of association can enhance study habits in older students by introducing desirable difficulties while encoding and retrieving information. Desirable difficulties or creating better conditions while simultaneously introducing a new difficulty level for better and more flexible learning is often linked with associative learning.

Some individuals may find that reading silently at home effectively aids in comprehending English literature, while others may benefit from studying in a library with fellow students or while listening to music. These preferences suggest that varying study environments can optimize learning effectiveness.

Furthermore, mnemonic devices such as acronyms, rhymes, and visual aids can improve the retention of information. For example, reading Victor Hugo’s epic novel “Les Misérables” may be complemented by watching a theater play or film adaptation.

While the previous mentions were about encoding pieces of information, spaced learning capitalizes on retrieving the information learned through timed intervals. You may check out our article about the Forgetting Curve for a glimpse of spaced learning.

In addition to consistently reviewing for a test, building connections between new knowledge and your schema is one of the most effective ways of learning and retrieving. See our Retrieval Practice Explained and The Leitner System for Studying articles for more tips and tricks on studying and remembering.

Associative Learning Beyond the Classroom

Associative learning also influences parenting, where reward systems, punishments (such as grounding or time-outs), and modeling shape children’s behavior, emotional responses, and cognitive development through associations between experiences, actions, and consequences.

Building upon the principles of Pavlov and Skinner, Albert Bandura bridged the gap from behaviorism to cognitivism with his Observational Learning, often referred to as the Social Learning Theory. Bandura’s Bobo-doll experiment revealed that children acquire attitudes, values, and behavioral styles by observing others’ examples (Bandura, 2008). In everyday life, children frequently learn by observing and imitating their parents’ behavior. For instance, a child consistently witnessing a parent practicing good manners may associate them with positive social interactions and exhibit them in broader social settings like school.

Associative learning also plays a role in understanding phobias and addressing anxiety. Studies suggest that conditioning contributes to the development of anxiety in childhood, as conditioning mechanisms are involved in the development of fears (Field, 2006).

In marketing, associative learning is leveraged to choose endorsers, optimise promotion strategies, and craft effective advertising. Celebrity endorsements, for instance, are often employed to create and reinforce associations between products, brands, and consumer responses (Till, 1998). Additionally, reward and discount programs, as well as online feedback, impact consumer behavior when making purchasing decisions.

While Associative learning profoundly shapes our behavior, values, and development. Facilitating learning through association, particularly in improving study habits, is a common and often unconscious practice. While the nature of learners and the level of learning may vary, establishing routines and creating environments through association consistently prove effective.

So, the next time you find yourself experiencing happiness or sadness triggered by a steaming bowl of soup or a Taylor Swift song, remember that it’s all thanks to the magic of associative learning, which, as Taylor herself would say, “I remember it all too well.”

References:

- Bandura, A. (2008). Observational Learning. The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781405186407.wbieco004

- De Houwer, J. & Hughes, S. (2020). The Psychology of Learning: An Introduction from a Functional-Cognitive Perspective. Cambridge: MIT Press. Retrieved from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2022.845616/full

- Christian, K.M. (2010). Cerebellum: Associative Learning. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Neuroscience, Academic Press. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780080453965001317

- Bryne, J.H. (2013). Learning and Memory. Fundamental Neuroscience, Fourth Edition. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/associative-learning#:~:text=Associative%20learning%20is%20the%20process,unconscious%20recognition%20of%20a%20contingency.

- Field, A.P. (2006). Is conditioning a helpful framework for understanding the development and treatment of phobias? Clinical Psychology Review, Volume 26, Issue 7. Retrieved from:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272735805001637

- Till, B.D. (1998). Using celebrity endorsers effectively: lessons from associative learning. Journal of Product and Brand Management. Retrieved from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/10610429810237718/full/html?fullSc=1&mbSc=1

Images:

2 thoughts on “What is Associative Learning?”

Comments are closed.